Impact of single dog pulling sports practice perceived by guardians on the human-canine bond and the dogs’ welfare

Here you can find my thesis about single dog pulling sports and the dog-human bond, produced to gain my ISCP Diploma in Canine Behavior. You can contact me for more information.

WACHS Mélissa

Thesis for the obtention of the Diploma in Canine Behavior of the International School for Canine Psychology & Behaviour

I. Introduction

Single dog pulling sports show a great increase in the number of people involved these last years, especially in certain countries such as France (Fédération des Sports et Loisirs Canins, 2022). These sports consist in the dog pulling his human, through an adapted harness and a bungee leash. The human can follow the dog with various means : walking, running, cycling, on a scooter, or on skis with or without a pulka on snow. These sports are called respectively : caniwalk or canihike, canicross, bikejoring, dog scooter, skijoring and pulka. They most of the time involve one human and one dog at a time, forming a practicing, sometimes competing pair. Any dog can participate in competitions, proven his growth is over, he is vaccinated, and he does not suffer from health issues. Concerning the human, competitions can be entered as young as toddlers, the distances being adapted depending on the ages, and young children being accompanied by an adult who manages the pulling force in the bungee leash of the child. The equipment has to be adapted to ensure it does not harm the dog, and approved to enter competition events. These sports are practiced as leisure, with competitions open to anyone who wishes to participate. They are derived from mushing, where dog teams pull sleds. For this purpose of carrying loads and humans, pulling has been performed by dogs for at least more than 1000 years (Kuhl, 2011). The aims have evolved, as this practice nowadays continues as a leisure or as lucrative touristic activities.

Despite the lack of scientific evidence, from my personal experience of over 15 years of practice of dog sports, the vast majority of dogs love to pull. And this taste for pulling is not reserved to some well-known breeds such as Siberian Huskies or Alaskan Malamutes. If some dogs need a little time to understand what is expected from them, especially if they were harshly trained to heel, they most of the time then engage with a lot of will into pulling. Indeed, dog teams during the Gold Rush in Alaska were already composed not only of indigenous dogs, but also of many imported dogs from other parts of North America or Russia. Therefore, various breeds and mixes were used, such as hounds, retrievers and Newfoundland-looking dogs. Later, by 1908, the best competing teams in the first All-Alaska Sweepstakes race in Nome were constituted of dogs presenting a uniformity in conformation and size (Coppinger, 1977, in Serpell, 1995). New breeds or mixes then emerged, selected for this purpose of sledding, their required aptitudes evolving depending on the type of effort they were asked to perform.

In our current societies, relationships between humans and dogs can be seen as a way of meeting human needs for companionship, friendship, unconditional love and affection, the increasing disconnection between people leading to deepening bonds with pets. This induces greater attention payed to pets health, and deeper emotional attachment (Boya et al., 2012). Indeed, in our postmodern world, the change from a utilitarian to an affective relationship with dogs can be seen as a response to the insecurities felt (Franklin, 1999, in Włodarczyk, 2016). Thus, Włodarczyk (2016) suggested that the primary motivation for participating in dog sports was the will to create a relationship where the dog shares the desire for interaction.

This perception of the dog by humans can influence the dog’s wellbeing. Indeed, welfare can be evaluated by measuring key dimensions which are : good feeding, good housing, good health, and appropriate behavior (Barnard et al., 2016), and humans considering their dogs to provide them with motivation and social support walk with them more frequently (Westgarth et al., 2014, in Hall et al., 2021). Another, more complete way to look at a dog’s well-being is to consider the Hierarchy of Needs (Michaels, 2015), which must be satisfied for a dog to maintain a state of physical and psychologic homeostasis (Clark et al., 1997, in McMillan, 2002). Regarding the very nature of single dog pulling sports, they could be a mean for dogs to increase their chances of having needs met from each layer of their hierarchy of needs : biological needs through physical exercise, social and emotional needs through gathering and connexion with their human, novelty when the competing or training pairs discover new places together. Force-free training could be implied, as it seems difficult to force a dog to run. Indeed, it is a voluntary act from him and if pulling the dog is strictly forbidden and sanctioned in competition, it also seems counter- productive.

Moreover, Andreassen et al. (2013) found a positive correlation between attachment to the dog and the amount of time the dog was walked. This was confirmed by Curl et al. (2016) who observed that guardians with a greater bond with their dog would walk them more and for more minutes, probably also taking into account their health issues, and their need for sniffing. Humans experiencing more pet attachment also reported more physical and mental health benefits (Hulstein, 2015).

The dog-human bond is itself influenced by several factors, including the amount of quality time spent with the dog and the polarity of the interactions. Indeed, it was shown that increased quality time spent with the dog improved the human-canine relationship, as well as the increase in positive interactions does (Clark & Boyer, 1993).

However, most of the studies undertaken focus on dog walking as the canine activity performed, whereas data available concerning other types of exercise, such as dog sports, is scarce (Hall et al., 2021). Other, qualitative studies concentrate on the mushers’ experiences with their dogs, such as in the work of Kuhl (2011). Very few studies concentrate on agility, and one study (Merchant, 2019), explores the experience of canicross, from an ethnographic perspective. No work was found analysing the dog-human relationship in single dog pulling sports.

The purpose of this study was to determine wether the practice of single dog pulling sports influences the human-canine bond, and how. The impact on dog welfare was also measured, and the influence on human welfare questioned, as both are interlinked and related to the quality of the human-canine bond.

II. Materials & methods

A. Assessment of dog welfare and human canine bond

Dog welfare was assessed regarding the fulfilment of biological needs, such as adapted feeding, healthcare, and physical exercise, but also emotional and social needs, through interactions with humans and other dogs. These are the first three levels of dogs’ needs. Mental stimulation, which is part of the cognitive needs, was also considered.

Dwyers et al. (2006), established a scale called the Monash Dog Owner Relationship Scale, in order to assess human-companion dog relationships. However, due to the uncertainty in the number of possible answers to the survey, and thus, the probable inoperability of the results, this scale was not used in this study. Instead, we used the respondents’ perception of their relationship with their dog, as well as possible indicators, such as behavioral observations from the guardians and the amount of shared quality time. Possible evolution in feeding, health checkups, duration and frequency of outings, perceived dog welfare by guardian and reasons invoked, behavior of the dog when he goes training, were evaluated to determine a possible effect on dog welfare.

B. Questionnaire

Based on the elements from the literature review, a questionnaire was designed and published on social media. The whole questionnaire can be found in annex. Questions were based on dimensions of the dog-human relationship identified in literature. They were aimed at measuring dog-related behaviors, perceived dog behavioral changes, perceived dog welfare, and characteristics of the dog-human relationship.

A combination of open and closed questions was used, in order to obtain both qualitative and quantitative answers, as the number of answers to be gathered was first uncertain. Open questions were related to perceived dog welfare evolution, the reasons for practising these sports, behavioral issues, perceived appreciation of this sport by the dog, perceived changes in dog- human relationship, and a last question where respondents were invited to write whatever they wanted to add. Answers to the qualitative questions were classified to sort out keywords and ideas and thus extract quantitative results. Closed questions were multiple choice questions with one or several answers possible.

To increase the chances for data collection considering our mean of dissemination of the questionnaire, the number of questions asked was kept to a minimum, and the impact of the practice of single dog pulling sports on the human was not assessed here, but only put into perspective with the possible repercussion on relationship with the dog.

C. Sample

The sample used was collected from an online survey, publicly published and shared on social media but aimed at dog owners who practice single dog pulling sports. It was filled by personal contacts, and also shared on dedicated groups. 134 answers were gathered between 17th and 21st February 2022.

III. Results

A. Dogs and respondents

11% of the participants were less than 25 years old, 44% between 25 and 34, 29% between 35 and 44, 12% between 45 and 54, and 4% over 55 years old. 83% of them were women while 17% were male. 83% lived in France, 7% in Canada, 3% in Belgium, 2% in Switzerland, 1,5% in Norway, 1,5% in Italy, 0,7% in Mexico and 0,7% in Finland.

38,8% declared having 1 dog, 29,1% 2 dogs, 20,9% 3 to 5 dogs, 9,7% 6 to 10, 1,5% 11 to 20 and none over 20 dogs. People having several dogs were asked to answer the questions concerning one of their dogs with whom they practice single dog pulling sports.

Many different breeds were represented in our sample. To simplify and have a better overview, they were categorized in : mixes, Siberian Huskies, which was a popular breed originally in pulling sports, other primitive dogs, mixes specifically created for the purpose of these sports, which comprise European Sled Dogs, Greysters, Eurohounds and Alaskan huskies, and Shepherds and others. For respondents who declared having several dogs and listed the different breeds, the numbers of dogs of each breed was redistributed in the previous categories listed. However, answers listing several breeds but no number could not be processed and therefore, were not taken into account. Owners of only one dog were guardians of shepherds (38,5%), primitive breeds (15,4%), mixes (15,4%), hunting breeds (9,6%), mixes created for these sports (7,7%), other dogs (7,7%), and huskies (5,8%).

67,91% of the respondents declared to have chosen their dog’s breed or mix because their personality could correspond to their own, 54,48% for his sportive abilities, 51,49% because they liked his physical attributes, 22,39% specifically for the practice of their sport, 10,45% that their dog is a rescue and they did not choose and 4,48% chose following their heart or feelings.

86,3% of the participants declared that their dog lives in the house, 13,0% in the house when themselves are home, and in a kennel when they are absent, 0,8% in a kennel. 22,4%% of the sample practice single dog pulling sports since less than a year, 13,4% since 1 to 2 years, 35,1% since 2 to 5 years, 15,7% since 5 to 10 years, 13,4% since over 10 years.

The most practiced sport is canicross, with 85,1% of the sample, then canihike or caniwalk (68,7%), bikejoring (56,7%), scooter (30,6%), skijoring (24,6%), sledding (19,4%), agility (17,9%), tracking or mantrailing (12,7%), kart (4,48%) and other sports (17,2%). The presence of multi dog pulling sports in our results is due to the fact that respondents practiced these sports and single dog pulling sports. 70,9% of the sample declared entering competitions, from which 49,5% regularly and 50,5% occasionally.

40,3% declared facing no behavioral issues, while 24,6% spoke about reactivity, 5,2% about anxiety, 3,7% about fear, and 1,5% about excitement.

B. Effects on dog welfare

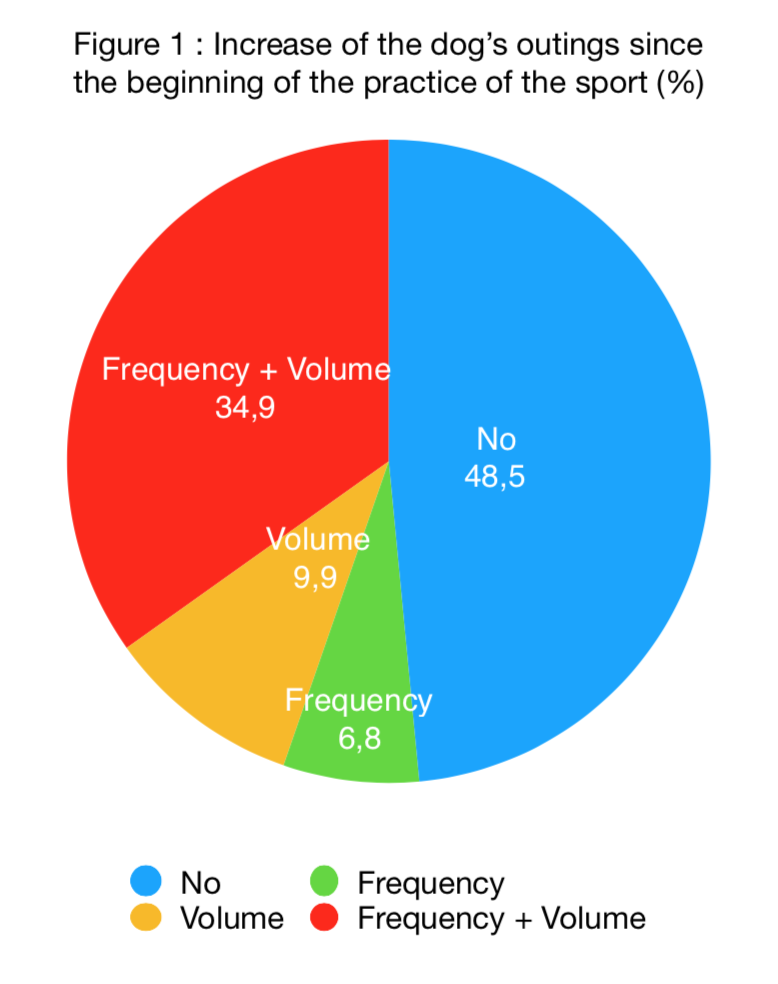

17,2% declared practicing and training specifically their dog for less than an hour per week, 32,8% 1h to 2h a week, 29,9% 2h to 4h a week, 18,0% over 4h, and only one person declared practicing only in competition. 34,9% of the participants declared having increased the frequency and volume of their dog’s outings, 35,6% did not change anything, 12,9% changed the nature of the outings, training their dog instead of walking him, 6,8% increased frequency, and 9,9% the volume (Figure 1).

51,9% of the participants declared that practicing these sports has become a way of life, 39,1% that they train themselves and their dog whatever the weather (avoiding too high temperature), which was not the case before, 27,1% that they wake up earlier to train when it is hot or before work, 21,1% that they go to bed later to train after work, 24,1% stated that they did not modify their rhythm of life.

77,6% of respondents stated that cold, rain and mud do not prevent them from training. 49,3% maintain the practice of the sport all year, except in extreme temperatures, 67,9% practice other activities with their dog in summer, 30,6% declared to be careful to cool their dog enough after training when temperatures are not so low anymore, 70,2% adapt their schedule to be able to practice as long as possible in the year.

37,1% did not begin another sport to prepare physically to dog sports, but 40,9% began running, 31,1% muscular reinforcement, 25% biking, 10,1% skiing, 0,8% swimming and 0,8% cardio training. 48,5% of the respondents began another sport to relieve their dog’s effort, 43,3% to suffer less when they practice with their dog, 23,1% to improve their race results. Some specified that they already practiced a sport but increased their practice since they began dog sports.

49,5% take their dog free running when they go train themselves, 40,8% train alone but take their dog out as much as before, 9,7% sometimes train alone instead of taking their dog out.

61,2% declared having changed their dog feeding or complementing after having begun the practice. 39,7% added complementation, 34,3% changed for a more energetic feeding, 19,2% increased quantities, 12,3% changed for raw feeding, prey model or household ration, 9,6% changed for better quality kibbles, and 5,5% specified that their dog already had an adapted feeding.

29,0% of respondents reported that their dog was already followed by an osteopath or another health professional other than a veterinarian, before they began to practice, 28,1% reported that they began to have their dog checked up as they began the practice, 16,4% that the dog was already followed but the frequency increased, 25,8% that the dog is still not checked up. Upon guardians who declared that the frequency of the checkups increased, 94% specified that it was preventive, and 6% curative.

Since the beginning of the practice of these sports, 87,6% of respondents did not notice a new behavioral issue, 20,9% spoke about excitement, 11,6% evoked reactivity or fear, 1,56% energy canalisation, 1,6% an increase in frustration, impatience and nervousness, 0,8% an increase of control. 62,2% noticed no behavioral issue resolution, 11,8% better interactions with other dogs, 7,1% a decrease in anxiety, stress or fear, 7,9% less nervousness or excitement, 3,9% better self control, 2,4% less destruction, and 1,6% better focus.

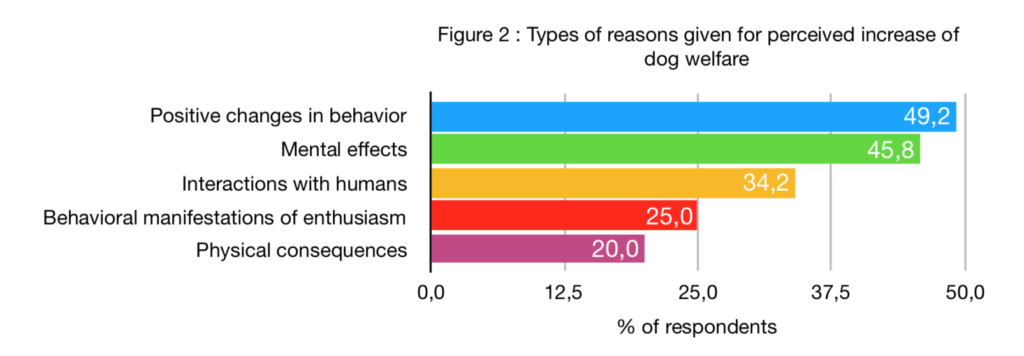

91,8% of respondents think that the wellbeing of their dog has increased since they began to practice a single dog pulling sport. Reasons expressed for this opinion were positive changes in behavior (49,2%), effects on mental stimulations (45,8%), provision of interactions with humans (34,2%), behavioral manifestations of enthusiasm (25%), and positive physical consequences (20%) (Figure 2). When the dog goes training, his behavior was described as excited (61,0%), happy (41%), impatient (21%), calm (3,1%), focused (2,3%), and motivated (1,5%).

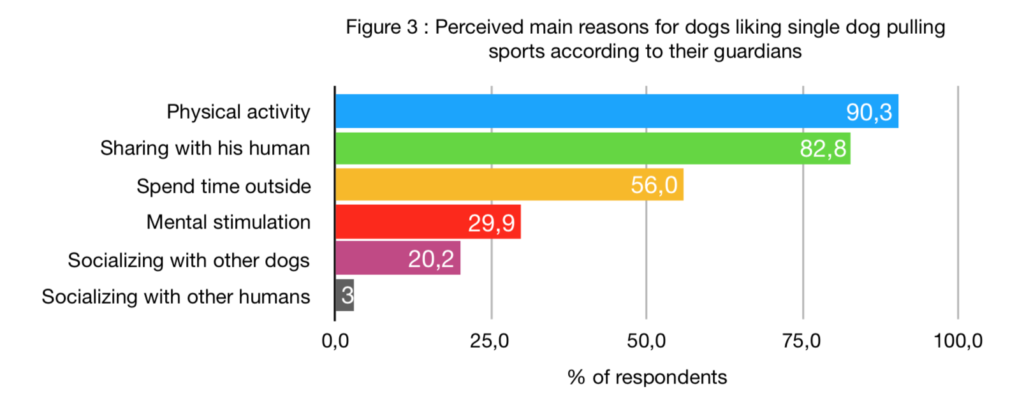

Reasons why guardians think the dogs appreciate the sport is that they look motivated (37,5%), happy (31,3%), excited (22,9%), impatient, 8,3%), focused (5,2%), demanding (5,2%), attentive (3,1%), and are born for it (3,1%). The elements that participants think their dog appreciate the most in this sport are physical activity (90,3%), sharing with his human (82,8%), spending time outside (56,0%), mental stimulation (29,9%), socializing with other dogs (20,2%), and socializing with other humans (3,0%) (Figure 3).

C. Impact on the human-canine bond

What respondents love more in the practice of these sports is sharing an activity with their dog (97,8%), exerting physically (71,6%), spending time outdoors (59,7%), socializing with other people (25,4%), and one person stated she did not like the sport and did it for her dog.

75,9% stated that they noticed a change in their relationship with their dog since they practice single dog pulling sports. 100% from the people who noticed a change think that their relationship improved and they are closer to their dog. None of them thinks that their relationship deteriorated. Among respondents who noticed a change, 81,5% wrote about complicity, closeness or trust, while 40,7% spoke about comprehension, communication, knowledge and attention. Among respondents who compete, 58,8% declared the practice of competition to increase even more the quality of their relationship with their dog.

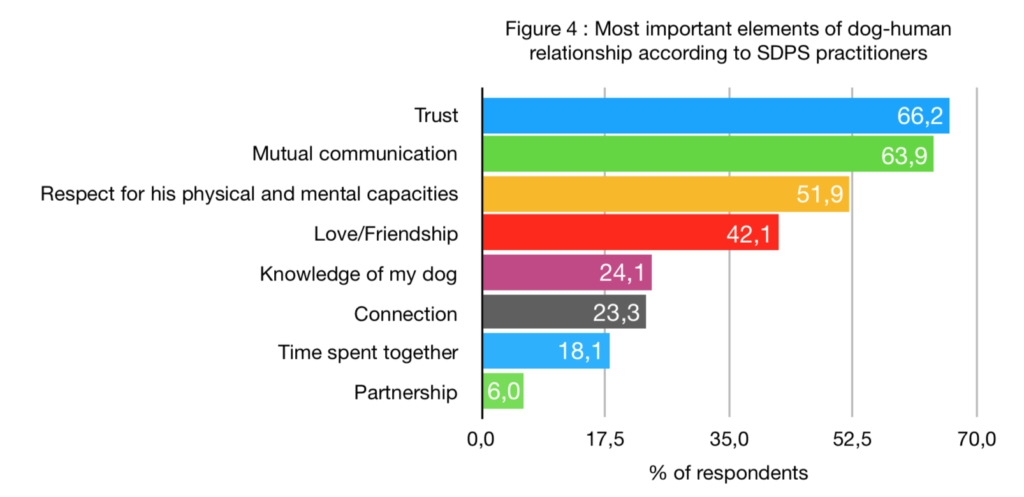

Trust was the element considered as most important in the relationship between practitioners and their dogs (66,2%), then comes mutual communication (63,9%), respect for their physical and mental capacities (51,9%), love/friendship (42,1%), knowledge of one’s dog (24,1%), connection (23,3%), time spent together (18,1%), partnership (6,0%) (Figure 4). Responses were limited to three, to extract the most relevant statements to guardians, and some of them had difficulties to choose as they wanted to select every possible answers.

50% declared spending over 3h of quality time each day with their dog, 32% 2h to 3h, 16,4% 1 to 2 h, and only 1,5%, less than 1h. 63,4% stated that the amount of quality time they spend with their dog has increased since they practice this sport.

Reasons for practicing are to share with one’s dog (47,1%), complicity with one’s dog (30,6%), sports practice (27,3%), pleasure (19,8%), dog’s pleasure or wellness (13,2%), dog’s physical exercise (13,2%), sensations (4,1%).

The most pointed out negative point of the practice of these sports is the difficulty to access certain places (26,4%), and the prohibition to access others (26,0%). Then the financial cost (9,4%), to have to train whatever the weather or their own energy or health (7,2%), the constraint to have several dogs to travel (5,3%), complicated daily management due to problems for the dogs of the household to get along with each other (3,0%), the amount of time it takes (2,1%), the lack of time for another sport practice without dogs (5,5%). 14,5% declared there was no negative aspect.

IV. Discussion

This study provides insights on the effects of the practice of single dog pulling sports on dog welfare and the human-canine bond.

Practitioners owning only one dog had mostly shepherds, others practicing with various types of dogs, showing the openness of the sport to any dog type. However, the type of dogs owned seems to show evolving tendencies following the number of dogs owned, the practice with dogs specifically bred increasing with the number of dogs. However, our data was not designed to answer this question and further investigation would be needed.

The dogs’ opportunities for physical and psychological stimulation depend largely on their guardians, and the latter show differences in exercising depending on their capacities, motivations, social environments and relationships with their dogs. Almost half of the respondents in our study train specifically their dog or practice single dog pulling sports over 2h a week. More than half of the respondents increased the outings of their dog in frequency, volume or both. Moreover, only 24% stated they did not modify their rhythm of life, others waking up earlier, or going to bed later, to train. More than half our sample stated that practising single dog pulling sports had become a way of life. Thus, guardians practicing single dog pulling sports tend to achieve the recommendations for dog owners to concentrate dogs’ activity to early morning or late evening, especially in hot weather (Daniels, 1983, in Hall et al., 2021), and dogs practicing those sports are likely to benefit from more time outside.

Almost 40% of practitioners train their dog and themselves whatever the weather (avoiding too high temperatures), which was not the case before. 70% adapt their schedule to be able to train as long as possible through the year. This shows that the practice of those sports can participate in meeting the dogs’ needs for physical exercise, and avoid their caretakers to wait for good weather for their dogs’ outings. Indeed, adult pet dog owners were shown to be less likely to exercise in poor weather conditions, such as ice, snow and rain, and weather is a reason to reduce the frequency and duration of exercise of companion dogs, whereas dog activity in free- roaming urban dogs increases in response to cloud cover, and is not impacted neither by rain nor snow (Daniels, 1983, in Hall et al., 2021), even though a shift could still be observed where dog walking becomes functional, to fulfil the dog’s need for exercise, instead of recreational (Hall et al., 2021). On the contrary, our study shows that guardians practicing single dog pulling sports were more likely to favor those weather conditions avoided usually by pet owners, to be able to train, avoiding high temperatures, for the longest period of the year possible. This confirms the results from Hall et al. (2021), showing that dogs competing in canine sports were less likely to experience activity decrease due to poor weather conditions. Furthermore, their guardians were more prone to cool their dogs after exercising in hot weather, and respondents in our survey confirmed they were attentive to this point, or to avoid training in high temperatures. Engagement in single dog pulling sports thus has a big positive impact on the frequency and volume of the dog’s outings and their maintenance throughout the year. Guardians also tend to take into account the dog’s sensitivity to heat.

Engagement in single dog pulling sports can also lead to changes in the dog’s physical health. Beyond the benefits of the increase of outings, an impact on feeding was also measured. More than 60% of the respondents changed their dog’s feeding after beginning the practice. Almost 40% added complementation to their dog, which can consist in vitamins, minerals, but also energy boosters or hydration drinks. 34% changed for more energetic feeding, almost 10% for better quality kibbles, and around 12% for raw feeding or household ration. These changes can result from exchanges and researches, and can thus also induce an increase in awareness and knowledge from the guardians on their dog’s needs. Indeed, participation in dog sports can cause practitioners to be more knowledgeable about some subjects such as dog feeding and exercise, as they have high levels of autonomy and strong views about their behaviors. Moreover, they often have a strong connection with other participants, which can include the sharing of information about feeding, body condition of dogs and exercise, sport specific or not (Kluess et al., 2021).

28% of respondents reported beginning to have their dog checked up by another health professional than the veterinarian, such as an osteopath, since they began to practice pulling dog sports. 16% of owners whose dogs were already followed indicated that the frequency of the checkups increased. In this latter case, a huge majority declared that the checkups were preventive. The practice of single dog pulling sports can thus induce the beginning of preventive osteopathic checkups. This can be a big improvement in a dog’s welfare as osteopathic issues can greatly impair a dog’s quality of life, by causing him pain. Moreover, osteopathic issues can be caused by a variety of activities or movements in daily life, independent of the practice of single dog pulling sports, such as playing with other dogs, jumping from a car, falling down the stairs, jumping to catch a ball, etc. Osteopathy is effective in sport horses for example to treat back pain (Vokietytė-Vilėniškė et al., 2021), and affects the sympathetic and immune systems in horses, inducing a decrease in heart rate, respiratory rate, and white blood cells count (Babarskaitė & Vokietytė-Vilėniškė, 2021). In humans, osteopathic manipulative treatment plays a significant role in regulating brain-heart interaction mechanisms (Cerritelli et al., 2021). In dogs, osteopathy showed very interesting results on the treatment of gastric pathologies (Agneray, 2003).

On the other hand, negative effects can be observed on the outings of the dog, but they remain scarce. Indeed, the practice of single dog pulling sports can lead caretakers to begin another sport practice in order to prepare physically to running with a dog. 37% of practitioners in our study did not begin a new sport in order to prepare physically to single dog pulling sports. The rest of them began running, muscular reinforcement, biking or skiing mainly. This new sport practice without dogs can lead some guardians to sometimes go out to train alone. However, our results showed that this concerns a minority of practitioners. Indeed, only 9% stated that this new sport practice conducted them to sometimes train without their dog, while others train alone but take their dogs out as much as before, or take their dogs free running with them. This seems important as lack of exercise can impact a dog’s quality of life, impairing his physical abilities, as well as his opportunities to fulfil biological needs and to be mentally stimulated. Indeed, studies have shown that less active dogs suffer more from extreme heat, because reduced activity impairs thermoregulation during exercise (Nazar et al., 1992, in Hall et al., 2021). Unsurprisingly, obesity in dogs competing in canine sports was shown to be lower than in pet dogs, attributed among other things to better awareness of body condition, lower overall rations fed, and the higher levels of engagements with activities (Kluess et al., 2021, in Hall et al., 2021).

Moreover, almost 50% began a new sport to relieve their dog’s effort while practising, 43% to suffer less and 23% to improve their results in competition. This shows that the practice of these sports influences human welfare as well, confirming that dogs can influence the amount of physical activity achieved by humans (Hulstein, 2015). Furthermore, among single dog sport practitioners who did not begin a new sport, a non measured but possibly consequent proportion already practiced sports before beginning single dog pulling sports, according to several qualitative answers received. Dog ownership was shown to have numerous positive effects on their guardians, improving their physical and mental health, reducing depression, increasing levels of oxytocin and decreasing blood pressure and cholesterol levels. Dogs also encourage their guardians to exercise regularly, decreasing the risk of cardiovascular disease (Hall et al., 2021). A study from Baldwin & Norris (1999) identified five categories of benefits for dog owners from practicing various dog sports : the dogs provided positive affect, participation caused enjoyment, relationship between the dog and the human and between the human and other competitors was perceived as enhanced, the dog provided exercise and relaxation in everyday life, and competition allowed testing of learned skills. This shows that the benefits of participating in dog sports goes far beyond exercising only. The human-canine bond could also influence the perception of relatedness, which is described by Ryan (1995) as the feeling of connection to other individuals. Moreover, dogs can also act as a social support system, influencing the amount of physical activity achieved by their humans (Stephens et al., 2012 ; Street et al., 2007, in Hulstein, 2015). Furthermore, the interspecies bond may be a factor encouraging and keeping engaged in dog sports, people who would otherwise be less active, as the comparison between sport and agility demography suggests (Hulstein, 2015).

Concerning behavior, 87% of the respondents noted no new behavioral issues since they began to practice. Others spoke about issues regarding excitement, reactivity or fear, nervousness, and frustration. On the other hand, 62% noticed no positive effect of the practice on their dog’s behavior. Others spoke about better interactions with other dogs, decrease in anxiety, stress or fear, less nervousness or excitement, better self control, less destruction, and better focus. However, when asked if they thought their dog’s wellbeing had increased since they began to practice single dog pulling sports, 92% said yes and almost half of them invoked positive behavioral changes, such as a decrease in anxiety, stress, fear, excitation or destruction, and an improvement of attention and interactions with other dogs. Other practitioners considered their dog’s welfare increased by the practice of single dog pulling sports due to provision of mental stimulation, provision of time to interact with their human, behavioral manifestations of enthusiasm by the dog and the observation of positive physical consequences on the dog. One respondent wrote that these sports allowed her dog to improve his relationship to humans in general, as he used to be reactive to men before. Another stated that his dog had understood that there were moments for interacting and others to relax, and was therefore less demanding in inappropriate situations. Several respondents expressed that their dog was closer and demanding for calm interactions after training or competing, such as resting together or cuddling. This is also very visible in one of my dogs, who, after a race, once he has cooled down, constantly demands to jump in my arms for a hug. Their increased attention towards their dog was also expressed by several respondents, as well as the given power to decide which makes the dog gain self confidence. One person wrote that her dog knows the days of practice and brings himself his harness to go training. Another stated that when she trains, her dog is partly free running, and when called back to be attached to his harness, he comes immediately. A respondent wrote that his dog heels from his own will when he wears the harness, waiting to be attached to pull.

What makes practitioners think their dog appreciates to practice is their interpretation of how they look : motivated, happy, excited, impatient, focused, demanding, attentive. What they think their dogs appreciate most in this sport is physical activity, sharing with their human, spending time outside, which are the same reasons they selected for their own practice of these sports, confirming that participants in dog sports often report similar benefits for their dogs and themselves. This benefits are perceived as motivators to engage durably in these sports (Farrell et al., 2015). Dog’s pleasure and dog’s physical exercise are also evoked. Other reasons raised for the dogs’ appreciation of these sports are mental stimulation, and socializing with other dogs.

The main negative points selected by respondents were difficulty and refusal to access certain places. Other reasons such as having to go out whatever the weather or one’s health, financial cost, amount of time it takes or difficulties to travel due to number of dogs were minors, and 14% even stated they found no negative point to the practice of this sport, which shows that the perception of the practice of single dog pulling sports by practitioners is highly positive, and negative points are mainly independent of the activity itself.

Half our sample declared spending more than 3h of quality time with their dog per day. This is likely to be more than the average population, even though no study was found giving the average amount of quality time spent by pet dog owners with their dogs. This could be due to the fact that people already spending time with their dogs then engaged in these sports. However, this is unlikely as over 60% of our sample declared that the amount of quality time spent with their dog increased since they began to practice. Thus, practitioners could also have already been spending more time than average with their dog, and this amount of time could still have increased with the beginning of the practice. Indeed, our respondents mainly stated the practice had become a way of life, illustrating the « culture of commitment » present in dog sports (Gillespie et al., 2002, in Klues et al., 2021). The great amount of time spent with the dogs is also an important element, as it permits mushers to get to know dogs and each one of them individually (Kuhl, 2011). Clark & Boyer (1993) showed that an increase in shared quality time led to better relationships between dogs and humans. Moreover, it was also shown that dogs and guardians sharing an active lifestyle complement each other, resulting in high owner satisfaction (Curb et al., 2013, in Hall et al., 2021).

If we look at the molecular level, a lot of research has been conducted on oxytocin and the impact of this hormone on bonding, including interspecific bonding. Indeed, oxytocin modifies our perception of our relationship, high levels of oxytocin being associated with the perception of a pleasant and interactive relationship with one’s dog. The oxytocin levels were shown to increase after interacting with dogs, in women (Miller et al., 2009). Moreover, high oxytocin levels in dogs are related to increased interaction with their guardians (Handlin et al., 2012). Thus, in dogs, oxytocin promotes positive social behaviors towards conspecifics and humans, suggesting the existence of an oxytocin-mediated positive feedback loop in dog’s social bonding (Romero et al., 2014). This is why, spending quality time with one’s dog generates a positive effect by increasing both the dog and human oxytocin levels, therefore reinforcing the bonding between them.

More than 75% of respondents said to have noticed a change in their relationship with their dog since they began to practice single dog pulling sports, the practice of competition increasing even more this positive effect. They all felt closer, with an improved complicity, more trust, attention, better communication, comprehension and knowledge of each other. Trust, communication and respect are the most important elements in their relationship with dogs according to respondents, which are the same words used to qualify their relationship with dogs by mushers. Indeed, building trust in the dogs is seen as key to a working relationship (Kuhl, 2011). A respondent even chose the word « symbiosis » to describe the relationship with his dog, and another described the fact of feeling both connected into a unique being. This intense bonding between people and their dogs was described by Hultsman (2012) about agility involved couples. Some mushers also state that their relationship with their working dog is deeper or stronger than the one they have with their companion dogs, the communication of thoughts, feelings and emotion between mushers and their dogs adding depth to their relationship (Kuhl, 2011). Merchant (2019), suggests that running with one’s dog instead of running alone modifies one’s perception of the environment. Moreover, she states that the behavior of the dog during the practice evolves with training towards a more focused one. She adds that canicross is a way for humans to engage in a sport which treats companion dogs as more than what their « biological machinery » offers, that is additional power, speed and endurance. The sharing of a « simultaneous sense of effort and reward » is also underlined (Laurier et al., 2006, in Merchant, 2019). This effect could be particularly observed during competitions, explaining why respondents mainly stated that competing increased the positive effect of the practice of these sports on their relationship with their dog. Merchant (2019) also claims that her dog and herself have become different through the practice of canicross.

Several respondents talked about their dog being born to pull or work, being happy to feel useful, or working being natural for them, highlighting the will to go of certain dogs and their need to run (Isacsson, 1996). Some authors such as Gilman (2003) believe that working dogs can live a better life as they do not rely only on affection but are able to perform what they were bred for, such as pulling. Even though his belief does not rely on any study, the high number of dogs, especially from working breeds, found in shelters, can be relevant of this effect (Kuhl, 2011), the lack of provision of opportunities to work and fulfil physical and cognitive needs possibly leading to behavioral issues.

One of the limitations of this study, is the use of a questionnaire and self-reported data, which induces uncertainty in the accuracy of the results. For example, survey respondents over- estimate the amount of activity they practice, which could also be true for dog sports (Westgarth et al., 2019, in Hall et al., 2021). Furthermore, the relationship between a dog and his human described here is, as said, the perceived relationship from the viewpoint of the human. Rehn et al. (2014) found no indication that the strength of the relationship felt by a human toward his dog is mirrored in the bond of the dog to his guardian. This is why, behavioral observations of the dogs were also taken into consideration in this study. However, they were also reported by the guardians, and thus conditioned to their interpretations.

Furthermore, as we found, dogs practicing single dog pulling sports are mainly companion dogs living in homes. Thus, the pursuit of dog sports induces a daily life and dog-human relationship, blurring the boundary between daily relationship and activity pursuit (Baldwin & Norris, 1999).

Further statistical analysis should be conducted to determine if the results are significative. Profiles of practitioners could also be established using correlation tests, as tendencies seem to emerge, for example between the number of years of practice and the number of dogs owned, the number of dogs owned and the breeds owned, with a possible increase of specifically bred dogs with the increase of the number of dogs. Correlations could also be found between the number of years of practice, and results concerning dog welfare, the amount of time of practice weekly and the perception of dog-human relationship. However, if an increase in dog’s welfare could be observed along with the increase in years of practice, due to better knowledge of dogs in general and their needs, perception by owners could reverse this effect, because of this increased consciousness of dogs’ needs, possibly followed by an increase in self requirements. Moreover, some respondents stated that they have been practicing for so long that they cannot really remember how was life without sport dogs.

V. Conclusion

This study suggests that, by modifying the type of exercise, increasing its volume and frequency, as well as potentially influencing the quality of resources fed and osteopathic checkups, and the amount of quality time spent with the guardians, the practice of single dog pulling sports influences positively the human-canine bond, and the welfare of participants, both canine and human. Single dog pulling sports dogs are companion dogs, living in homes with their guardians. Beyond the warmth of a home and loving caretakers, they can enjoy an active life, fulfilling their various needs and providing them with enjoyment, possibly more than certain companion-only dogs.

References

Agneray, F. (2003). Ostéopathie et troubles gastriques chez le chien. Doctoral Dissertation.

Baldwin, C. K., & Norris, P. A. (1999). Exploring the Dimensions of Serious Leisure: “Love Me— Love My Dog!” Journal of Leisure Research, 31(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/00222216.1999.11949848

Babarskaitė, G., & Vokietytė-Vilėniškė, G. (2021). Osteopathic manual therapy effect on sympathetic and immune systems. 16th International Scientific Conference STUDENTS ON THEIR WAY TO SCIENCE (Undergraduate, Graduate, Post-Graduate Students) Collection of Abstracts, 33.

Barnard, S., Pedernera, C., Candeloro, L., Ferri, N., Velarde, A., & dalla Villa, P. (2016). Development of a new welfare assessment protocol for practical application in long-term dog shelters. Veterinary Record, 178(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.103336

Boya, U. O., Dotson, M. J., & Hyatt, E. M. (2012). Dimensions of the dog–human relationship: A segmentation approach. Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing, 20(2), 133–143. https://doi.org/10.1057/jt.2012.8

Cerritelli, F., Chiacchiaretta, P., Gambi, F., Saggini, R., Perrucci, M. G., & Ferretti, A. (2021). Osteopathy modulates brain–heart interaction in chronic pain patients: an ASL study. Scientific Reports, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-83893-8

Clark, G. I., & Boyer, W. N. (1993). The effects of dog obedience training and behavioural counselling upon the human-canine relationship. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 37(2), 147– 159. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-1591(93)90107-z

Curl, A. L., Bibbo, J., & Johnson, R. A. (2016). Dog Walking, the Human–Animal Bond and Older Adults’ Physical Health. The Gerontologist, gnw051. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw051

Dotson, M. J., & Hyatt, E. M. (2008). Understanding dog–human companionship. Journal of Business Research, 61(5), 457–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.07.019

Farrell, J. J. M., Hope, A. E., Hulstein, R., & Spaulding, S. J. (2015). Dog-Sport Competitors: What Motivates People to Participate with Their Dogs in Sporting Events? Anthrozoös, 28(1), 61–71. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279315×1412935072201

Fédération des Sports et Loisirs Canins. (2022, February 19). Accueil. Retrieved 28 February 2022, from https://www.fslc-canicross.net

Hall, E. J., Carter, A. J., & Farnworth, M. J. (2021). Exploring Owner Perceptions of the Impacts of Seasonal Weather Variations on Canine Activity and Potential Consequences for Human–Canine Relationships. Animals, 11(11), 3302. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11113302

Handlin, L., Nilsson, A., Ejdebäck, M., Hydbring-Sandberg, E., & Uvnäs-Moberg, K. (2012). Associations between the Psychological Characteristics of the Human–Dog Relationship and Oxytocin and Cortisol Levels. Anthrozoös, 25(2), 215–228. https://doi.org/ 10.2752/175303712×13316289505468

Hulstein, R. (2015). Dog sports: a mixed methods exploration of motivation in agility participation. Doctoral Dissertation.

Hultsman, W. Z. (2012). Couple involvement in serious leisure: examining participation in dog agility. Leisure Studies, 31(2), 231–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2011.619010

Isacsson, A. D. (1996). Sled dogs in our environment| Possibilities and implications | a socio- ecological study. Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers, 3581.

Kluess, H. A., Jones, R. L., & Lee-Fowler, T. (2021). Perceptions of Body Condition, Diet and Exercise by Sports Dog Owners and Pet Dog Owners. Animals, 11(6), 1752. https://doi.org/ 10.3390/ani11061752

Kuhl, G. (2011). Human-Sled Dog Relations: What Can We Learn from the Stories and Experiences of Mushers? Society & Animals, 19(1), 22–37. https://doi.org/ 10.1163/156853011×545510

McMillan, F. D. (2002). Development of a mental wellness program for animals. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 220(7), 965–972. https://doi.org/10.2460/javma. 2002.220.965

Merchant, S. (2019). Running with an ‘other’: landscape negotiation and inter-relationality in canicross. Sport in Society, 23(1), 11–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2018.1555212

Miller, S. C., Kennedy, C. C., DeVoe, D. C., Hickey, M., Nelson, T., & Kogan, L. (2009). An Examination of Changes in Oxytocin Levels in Men and Women Before and After Interaction With a Bonded Dog. Anthrozoös, 22(1), 31–42. https://doi.org/10.2752/175303708×390455

Michaels. L. (2015). Hierarchy of Dog Needs [Illustra1on]. hkps://HierarchyofDogNeeds.com

Rehn, T., Lindholm, U., Keeling, L., & Forkman, B. (2014). I like my dog, does my dog like me? Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 150, 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2013.10.008

Romero, T., Nagasawa, M., Mogi, K., Hasegawa, T., & Kikusui, T. (2014). Oxytocin promotes social bonding in dogs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(25), 9085–9090. https:// doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1322868111

Serpell, J. (1995). The Domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behaviour and Interactions with People (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press.

St. Ours, K. (2019). How Mushy Are Mushers? A Study in (Narrative) Empathy. ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment, 27(1), 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1093/isle/ isz109

Vokietytė-Vilėniškė, G., Mataitytė, S., & ŽIlaitis, V. (2021). Effectiveness of osteopathic treatment on equine back pain : pilot study. 16th International Scientific Conference STUDENTS ON THEIR WAY TO SCIENCE (Undergraduate, Graduate, Post-Graduate Students) Collection of Abstracts, 47.